Puerto Rico certainly isn’t the first country that comes to mind when one thinks of great Latin American cheese producers. In fact, it doesn’t come to mind at all. Here in the States, you’re probably more likely to win the lottery or be struck by lightning than to find a cheese stamped “Hecho en Puerto Rico” in your local grocery store. Until recently, the odds haven’t been much better on the island itself: imported, wax-encased wheels of gouda, wedges of manchego, and blocks of cheddar are widely available, but queso del país is harder to find unless you happen to come upon a roadside stand selling family-made queso fresco in the towns of Lares, San Sebastian, or Hatillo.

Wanda Otero is hoping that won’t be the case for much longer, however. If Otero has her way–and a lot of people are supporting her because they believe she will–domestic cheeses will be both as popular and easy to find in Puerto Rico as imports within a few years. And maybe, just maybe, they’ll even be available in your local mainland grocery store, too.

Otero, a microbiologist by training, founded Quesos Vaca Negra in Hatillo, Puerto Rico in 2010. While she was doing just fine in her career as a specialist in milk analysis and quality control, Otero believed she could apply her training in a different, and more delicious, way. “I love raw milk, aged cheeses,” she says, “and Puerto Rico just doesn’t have them.” The cheeses produced on the island–most by small family businesses–are fresh, semisoft, non-aged varieties that tend to have a relatively static flavor profile. Otero saw an opportunity: seize on the growing popularity of locally-sourced foods, and those free of growth hormones and other harmful additives, to produce aged, raw milk cheeses practically in her own backyard.

Though the start-up phase of Quesos Vaca Negra was not without its challenges, some of which Otero still grapples with today, the microbiologist-turned-cheesemaker’s timing was just right in many ways. The Puerto Rican palate was beginning to diversify, with more Boricuas willing to experiment with novel tastes. At the same time, the number of upscale restaurants on the island was expanding exponentially, as were the growing number of international visitors considering Puerto Rico a food destination, thanks to increasingly popular food festivals, such as Saborea and SoFo. Key eateries, among them Peter Schintler’s Marmalade in San Juan and the restaurants of several high-end hotels, including Dorado Beach, a Ritz-Carlton Reserve, and St. Regis Bahia Beach Resort, began featuring Quesos Vaca Negra on their menus, and major supermarket chains on the island began selling Quesos Vaca Negra as well.

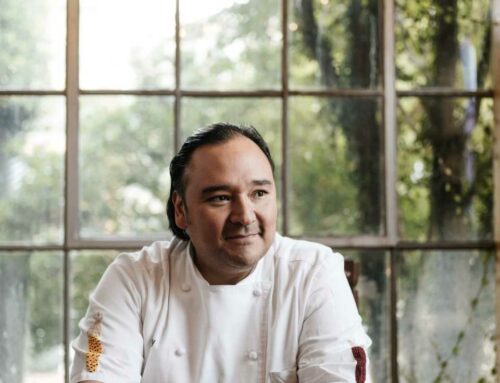

Chef Juan Jose Cuevas of 1919 Restaurant at the Condado Vanderbilt Hotel in San Juan, procures all five of the cheeses Quesos Vaca Negra currently produces. Four of the five are used for cheese plates and tastings; the other, Capaez, is used for cooking. “Wanda really was the pioneer for the cheese industry in Puerto Rico,” said Cuevas. “She realized that the island had access to such great dairy and began producing aged cheeses that compete in flavor with cheeses all over the world.” Because the chef’s culinary philosophy is to prepare “world-class cuisine, locally rooted,” Cuevas considers Quesos Vaca Negra an ideal vendor. “I love that it is a 100% Puerto Rican product,” he said.

That’s a point of pride for Otero, too, but it took a lot of patience and persistence for the business to get where it is today. Despite her professional bona fides as a microbiologist who had extensive experience working with milk, she says the Department of Health took a year to approve Quesos Vaca Negra’s operations. Funding was slightly easier; Otero believes being a female entrepreneur was actually advantageous, as the Small Business Administration provides funds and technical business assistance for female and minority entrepreneurs, and she has benefited from both. Her extensive experience and contacts in the dairy industry were invaluable, too; she barters her services as a quality control expert for the raw milk Quesos Vaca Negra uses to make its cheeses.

One of Otero’s biggest challenges right now is keeping pace with demand. She and her four employees produce 500-800 pounds of cheese a week. That’s a lot of queso, especially for a small producer making five different varieties, but she’d like to be able to produce even more. Doing so is difficult without additional employees, and it’s tough to hire additional staff when her costs are surprisingly high. “People wonder why the cheese is so expensive, especially since it’s from here,” she says, “but the distributor adds 25% [on top of my cost] and the supermarket adds 25% more,” she explains. Containing costs so she can hire more staff to combat Puerto Rico’s double-digit unemployment rate and expand her own operations is an item that continues to sit on the top of her to-do list.

That list is as long as Otero’s ambitions. Not content with just producing Cabachuelas (an intensely flavored cheese with hints of truffle and mushroom); Monserrate (a firm, yellowish-golden cheese, given its hue thanks to achiote); Ausubal (a firm, balanced cheese, easy on the palate); Capaez (a delicately flavored, intense yellow cheese with a buttery aroma); and Montebello (a yellowish cheese that nearly dissolves on your tongue), Otero intends to begin producing yogurt in February.

“Most yogurts have too much sugar, too many additives,” she said. “I want to produce a more balanced, natural yogurt.” And as if that’s not enough, Otero is also completely committed to continuing a series of activities intended to educate locals and visitors about Puerto Rican cheese. Make-your-own-cheese workshops and tastings are a regular event at Quesos Vaca Negra; for $60 for individuals/$80 per couple, visitors learn about the cheese-making process by rolling up their sleeves and working curd as Otero talks about Puerto Rican dairy farms and the general properties of aged cheeses.

For their efforts, visitors will take home a one-pound wheel of cheese they make and flavor themselves (though, it should be noted, the cheese has to age two months, so you’ll either need to return to pick it up or request Otero ship it to you). The events are incredibly popular; 19 people attended the December workshop, even though it was right around the holidays. In addition to workshops, Otero hosts free “Casa Abierta” days, when visitors can show up for cheese and wine tastings and can purchase Quesos Vaca Negra’s cheeses at factory prices. (Events are announced on the company’s Facebook page.)

Eventually, Otero might devote some of her efforts to establishing a “denominación de orígen” designation for Puerto Rican cheese; it’s an idea that has occurred to her, of course, and she’s done some preliminary research about what a “D.O.” would require. For now, though, she’s got her hands full as the chief, cook, and bottle washer of Puerto Rico’s first aged cheese operation, trying to keep up with growing demand from chefs and cheese lovers who are happy to see the profile of Puerto Rican cheese expanding beyond homemade queso fresco.

![Making Mealtime Matter with La Familia: Easy Sofrito [Video]](https://thelatinkitchen.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/10/sofrito-shutterstock__0-500x383.jpg)

![Easy Latin Smoothies: Goji Berry Smoothie [Video]](https://thelatinkitchen.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/12/goji_berry-shutterstock_-500x383.jpg)

![Fun and Fast Recipes: Fiesta Cabbage Salad [Video]](https://thelatinkitchen.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/11/fiesta_cabbage_slaw-shutterstock_-500x383.jpg)