On the first full day of Lima, Peru’s rapidly expanding annual gastronomic festival, now in its fifth edition, the crowds didn’t arrive until the afternoon. Then they never left. The second day at Mistura, El Chinito, a sandwich stand had a line 100 deep by 11am, though most other stands didn't pick up until around noon. On the first Saturday 31,000 people came to eat. On Sunday, 41,000.

There is an energy surrounding cuisine in Peru, one that is redefining Peruvian society as a whole. Mistura exemplifies this notion better than any single restaurant or chef ever could. While Peruvians have always been proud of their food, something bigger than pride is occurring. Though the festival has become a spectacle of sorts with sponsored pavilions and nightly concerts that bring in top musical acts, it's hard to ignore the profound effect the event has in the country's some 80,000 young chefs who come from all parts of the country wearing their white jackets, and the many producers of the country’s vast array of unique ingredients dressed in the colorful clothing of their native villages who came to sell their food in the Gran Mercado. The festival, while introducing rural restaurants and products to a national audience, has been become a powerful force in not only teaching Peruvians about the diversity of the cuisine in their own country, but showing some of the world’s great chefs the extent of the effect of which food can have on a country.

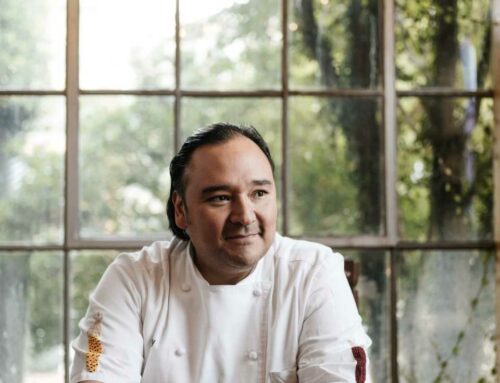

“It was a surprise,” said Joan Roca, the chef of Girona, Spain’s El Cellar de Can Roca, number two on San Pellegrino’s list of the world’s best restaurants. “It’s incredible what is happening here,” he told me.

In the main auditorium, you were surrounded by panels decorated with extreme close ups of quinoa grains. Attendance in the presentations, which were held every few hours, was almost always at capacity. Here regional chefs were invited to take part in Top Chef-like contests that focused on concepts like the best sustainable ceviche, which utilized non-threatened fish and encouraged Peruvians to seek out variety in their national plate, rather than simply eat the dish with the standard sole or seabass.

“We need to start using different varieties of fish,” said chef Adolfo Perret, of the restaurant Punta Sal. “A Chita used to cost 12 soles. Now it's 35. Just because there isn't any."

Other courses gave new looks at cuy, or guinea, pig, as well as paiche, a giant Amazonian fish whose sustainable farming is now making it readily accessible on the coast and even abroad. Great chefs from around the country gave inside looks of their preparations, showing the culinary obsessed audience how they too can advance Peruvian cuisine. For instance, Ache's Hajime Kasuga revealed new developments in Nikkei cuisine, while his barman taught a course in molecular cocktails. For the young chefs and restaurant owners from Peru’s provinces who lack exposure to the national scene, it means everything.

Peruvian chefs were not the only teachers, however. While the average Peruvian chef lacks the funds to travel abroad, let alone dine in a top restaurant, bringing in chefs such as Roca, Brazil’s Roberta Sudbrack, or Australia’s Peter Gilmore is helping shape a global understanding of cuisine in the country. Questions from the audience allowed students and festival attendees the chance to interact with these chefs. Some asked technical questions about their preferred knives, while others presented their own ideas to these chefs about what they have found makes the best ceviche, be it a certain aji pepper, the acidity of a lime from a certain region, or the particular fish or shellfish they use, be it from the mangroves of Tumbes or the rivers of Ucayali.

Still, it’s the food here that brings everyone together, and even with the 600,000 attendees who came to the Campo de Marte this year, it is abundant and readily accessible at every angle. El Gordo, a small restaurant from Caraz sold a rarely seen type of ceviche, called atallau she, which uses charqui, dried meat (in this case pork), instead of fish. There was ice cream made from quinoa and an entire pavilion dedicated to artisanal chocolate producers, many of them from indigenous co-ops. There were juanes from Tarapoto in the Amazon. One of the city’s iconic combis was turned into a modern food truck, while another was turned into a bar. Pork was a particular highlight and drew the longest lines. It was cooked in metal cylinders or roasted slowly over open flames. One vendor cooked his pork skin so crispy that I saw him roll a plate right through, making a delicious cracking sound. Dozens of rural producers brought a rainbow of colored quinoas and other Andean grains like kiwicha, which were a focal point this year. Many were traveling out of their provinces for the first times in their life. They see their products being celebrated in a big way on an increasingly international stage, giving them a pride that they take back with them in their rural villages and farms, a circular love that will soon finds its way back on to everyone's plate.

All photos courtesy of Nicholas Gill

![Making Mealtime Matter with La Familia: Easy Sofrito [Video]](https://thelatinkitchen.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/10/sofrito-shutterstock__0-500x383.jpg)

![Easy Latin Smoothies: Goji Berry Smoothie [Video]](https://thelatinkitchen.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/12/goji_berry-shutterstock_-500x383.jpg)

![Fun and Fast Recipes: Fiesta Cabbage Salad [Video]](https://thelatinkitchen.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/11/fiesta_cabbage_slaw-shutterstock_-500x383.jpg)