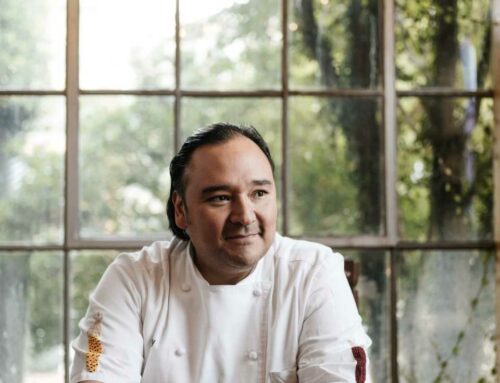

Dubbed Chile’s native son by his restaurant peers, Rodolfo Guzman is taking the farm-to-table concept to a whole new level. He is one of Chile’s most famous chefs, at the helm of Boragó, a restaurant where everything served is 100 percent Chilean and, most likely, sourced by the chef himself.

After an injury forced him to rethink his career path, he thought about what he loved most. There were two answers: Chile and food. “When I was 20 I was injured, and at that moment, I had to decide what I really wanted to do with my life," said Guzman. "Since food had always been a part of my childhood, and it was the one thing I kept with me growing up, I turned to that. “

After graduating from culinary school, he trained under Andoni Luis Aduriz at Mugaritz in Spain. While there, he decided to take the idea of cooking and serving food one step further. He became interested in the relationship between food, health, mood and culinary technique. His culinary focus became centered on the relationship between mood and food, but the history of his native land and all it has to offer was his grounding force.

“Chilean tradition is all I know," Guzman said. "It’s what I grew up with. It’s my childhood, my memories. So obviously, it’s where I source most of my techniques. Using native cooking methods, or at least looking to them for inspiration.”

Guzman took these methods to the kitchen when he opened Boragó in 2007. Today, it is one of Latin America’s best restaurants. The year it opened, Boragó was named Best New Restaurant by El Mercurio's Wikén magazine and since then has been ranked Number 8 on San Pellegrino's The World’s 50 Best Restaurants in Latin America list and labeled The Best Restaurant in Chile.

Yet, in Santiago, Guzman says Boragó doesn’t get the response you would think.

“Here in Santiago when people go out they want to eat fancy, French food," Guzman said. "But obviously what we do is something different. We wanted to create a menu around products and foods you can only find here in Chile. At first, we had some trouble with the people in Santiago. They thought we were crazy. Although now that we've gotten a bit of recognition, people are beginning to come in and be proud of what their country has. And people from out of the country have begun to come in to see a bit of what Chile has to offer. So in that respect the response to us has improved. People just want to come and eat what we serve now.”

Next, how Guzman works to serve Chile on a plate… [pagebreak]

And what they are serving is, literally, Chile on a plate. Guzman believes that Chileans are “culinary multimillionaires“ and takes advantage of the bounty of the land. He and his kitchen team regularly head out on foraging excursions to find the very best and freshest ingredients. There is no limit on where they will go.

One day it might be 3,000 miles above sea level cutting wild fruit and another they may find themselves looking for branches in Rica Rica or gathering wild edible flowers that only blossom two weeks per year. It’s when he finds what he likes that he decides what will be on Boragó’s menu.

“If we go foraging and find 5 kilos of sunfires, then we've sourced sunfires for the next week," Guzman said. "It’s as simple as that. Where we find the best stuff, we take it. The mushrooms grow, so we cut them. If they don't grow because it’s been too dry, we change the plate. “

If product isn’t accessible, Guzman finds where it is best. For example if a rainstorm prevents fishermen from going out safely along the coast of Santiago, he will fly fish in from Easter Island, “because its the place that can give us the best product, in that moment.”

Famous for his passion and love of Chile as much as he is for his innovative cuisine, Guzman could be one of the country’s most dedicated proponents of its food, going so far as to cook on hot stones and smoke food with native woods.

“This country has a very wide culture behind food, especially in the countryside," Guzman said. "The Mapuches culture is more important now than ever. We have a big historic culture to pull from and there are traditions that still carry on, and will continue to carry on. All we're missing is the support.”

Eating is just one way to experience the Chilean traditions. Boragó – which seats 48 in the winter and 52 in summer – has had, at times, as many as 30 people in the kitchen. “But not because we have a ridiculous mise en place list, “ Guzman explains. “More, it’s because we want to share the knowledge that we have, and the endemic products with people. Eating is one way to experience them, but working with them, cleaning, cooking, tasting them, is another. This is something that, if we want Chilean food to grow, and we want people to become aware of their surroundings, is important to teach.”

Rodolfo Guzman will happily teach when it comes to the food of Chile, but don’t expect him to go beyond the kitchen.

“I don’t pretend to tell stories, just try to explain the food itself," Guzman said. "We want to tell the story of a berry that in the world only grows in a corner of the Patagonia, for two weeks a year. We care about where the product comes from and when it was cut from the ground. It’s that simple.”

![Making Mealtime Matter with La Familia: Easy Sofrito [Video]](https://thelatinkitchen.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/10/sofrito-shutterstock__0-500x383.jpg)

![Easy Latin Smoothies: Goji Berry Smoothie [Video]](https://thelatinkitchen.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/12/goji_berry-shutterstock_-500x383.jpg)

![Fun and Fast Recipes: Fiesta Cabbage Salad [Video]](https://thelatinkitchen.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/11/fiesta_cabbage_slaw-shutterstock_-500x383.jpg)