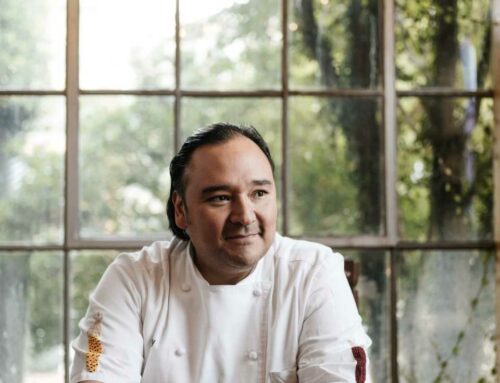

Chef Kevin Roth plucked a ripe prickly pear from a tree in the garden that surrounds his restaurant. “I’m going to be picking these out the whole day,” he said smiling, referring to the invisible needles that will cover his fingertips if he’s not careful.

Roth is the owner of La Estación, a five-year-old barbecue restaurant converted from a former gas station, which he runs with his wife Idalia García in Fajardo, on the east coast of Puerto Rico. Here the couple celebrates their dual identity and the love they share for repurposing, creating inventive Nuyorican dishes with local, sustainable produce that gives new life to traditional Puerto Rican ingredients and techniques.

“I never worked in a barbecue restaurant with barbecue equipment. So it’s not really any particular style. It’s not like a Texas style that’s dry or the North Carolina style where they put the vinegary sauce on the side. It’s just kind of our own thing,” said Roth.

Roth marinates all the meats overnight and then seasons them with a house dry rub made of freshly toasted and ground spices of chili peppers, coriander, cumin, ginger, and other secret ingredients. He brushes them with a guava barbecue sauce, basting them before firing up the meats in the custom-built smoker and grills he designed. During the busy season and the holidays, he prepares Puerto Rican lechon by roasting his squash-and-watermelon-fed pigs to a golden crisp in the back of an old burnt-down Jeep he flat bedded and transformed into a rotisserie.

“We put charcoal in the corner and as we need it, we move the charcoal to the different areas of the pig so that it cooks evenly. It does have its own motor and it spins, which makes it easier. But it cooks it really well,” he said, explaining the process.

Roth looks like the quintessential Brooklyn chef. He wears a trimmed beard, a piercing on his earlobe, and a miniature pig that hangs from a thick silver chain around his neck. His Brooklyn grit is as permanent as the black ink that stretches out around his elbows.

Next up, how a Brooklyn couple made it to the Caribbean…

[pagebreak]Before coming to the island, Roth and his wife lived in a neighborhood he described as a “very Puerto Rican area of Brooklyn”. They hosted barbecues in their backyard and grew strawberries and tomatoes out of discarded five-gallon lard containers from the neighborhood Chinese-Puerto Rican restaurant. Every day, he would swing by and pick them up on his way home from work.

His wife, who was working out on their day off, enters the restaurant. She has wild curly hair and an effervescent laugh. She describes how La Estación reflects their old Brooklyn life.

The blooming grounds surrounding La Estación are home to a tropical sanctuary of herbs and plants. Sprightly parcha and quenepa trees form a canopy of incandescent green, delicate jasmin perfumes the air, red heliconias dangle like vibrant sculptures. Oregano bruja, basil, and ajicito dulce, a native sweet pepper, grow near the earth, each ready to be used on a whim.

This green lushness is a stark contrast to the rusty remnants of the gas station left behind. An old Esso sign hangs above the stove, a steering wheel suspended from the ceiling, a New York license plate a reminder of their past life.

Outdoors, concrete tables with straw umbrellas invite those stopping by for a quick pincho and a beer. Adirondack chairs made of recycled cedar and a family table sit beneath strung lights that give the restaurant its warm soft glow when the sun goes down and the music of the singing coqui frogs ride the breeze.

In the air-conditioned refuge indoors, a collection of personal knick-knacks line the shelves; a photo of a young Marc Anthony, an oversized wooden mortar, a pair of black Converse, mural of exotic tropical flowers, the couple’s Schwinn bicycles hang from the ceiling. “We like to collect stuff. We don’t like to throw things away. We put a lot of our personal stuff into the restaurant. It’s resonated with the clientele and they feel it too. They feel that it’s personal. They can feel that there’s a soul behind the restaurant,” Roth explained.

Next up, the philosophy behind the food at La Estación…

[pagebreak]Half of that soulful quality comes from Garcia, who started her food career in Diner, a Brooklyn restaurant she praised as one of the pioneers of the slow food movement. The restaurant was a converted 1920s dining car that served a small ingredient-driven menu of French bistro classics.

“I’m not into that kind of food, what’s it called? The style of food that has all the foams? Molecular gastronomy! Ugh! It’s this but it’s not that. I’m really into very pure food where it is what it’s supposed to be,” she said.

This is exactly what dwells at the heart of La Estación: Serving simple comfort food with an emphasis on local. Roth and Garcia smoke their meats with mango wood and quenepa wood, one of Puerto Rico’s abundant natural resources, and use charcoal instead of gas.

“A lot of the products that make our restaurant the most interesting are the products that aren’t really available on the market. You can’t go and buy them. Like grosellas, cerezas, guanabanas, and quenepas. Those are the things that attract me to it, as a chef,” said Roth.

Roth will top a wahoo ceviche with Puerto Rican piragua, or shaved ice most commonly sold in street carts and drizzled with flavored syrups. He’ll flavor his piragua with these grosellas (local gooseberries) and jalapeño.

Roth and Garcia get a lot of their fruits and herbs from the garden, but they also rely on a small group of local suppliers to source their pigs, vegetables, fish, and charcoal.

“That was one of our biggest challenges in the beginning. Establishing the relationships with fishermen, farmers, and stuff like that [Roth: especially being outsiders] And it’s still one of the reasons why our menu is so small and the core menu depends on what we get. Because one week you can get how many pounds of tuna [Roth: and then the boat leaves] and you don’t get it for a while. Or it’s Semana Santa and none of the fishermen decide to go out to fish. They’re like ‘No, it’s Semana Santa, I’m not going fishing. It’s a holiday,’” explains Garcia.

“But at the same time, it’s ultra rewarding when the guy walks in and the fish is 30 minutes old and you just look at it and you’re like ‘Wow, look at that,’” said Roth.

Roth grills and serves his yellowtail snapper like no one else. He rubs it down with fresh ground chilies, mustard powder, and ginger. He grills it whole and serves it scored on a smooth slab of cedar with juicy pineapple salsa, a side a spicy green papaya salad, and piping hot Puerto Rican arepas.

The menu – which once consisted of cheeseburgers, hot dogs, pinchos, and ribs – has evolved as much as the restaurant itself. “Before this we had a 10×20 kiosko on that side. She was there and we had this door open. We had a grill set up here and a Mom and Pop refrigerator. That’s how it started,” said Roth, as he cut the prickly pear on a red Formica table, their old dining table in Brooklyn.

![Making Mealtime Matter with La Familia: Easy Sofrito [Video]](https://thelatinkitchen.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/10/sofrito-shutterstock__0-500x383.jpg)

![Easy Latin Smoothies: Goji Berry Smoothie [Video]](https://thelatinkitchen.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/12/goji_berry-shutterstock_-500x383.jpg)

![Fun and Fast Recipes: Fiesta Cabbage Salad [Video]](https://thelatinkitchen.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/11/fiesta_cabbage_slaw-shutterstock_-500x383.jpg)